Skydive With eBPF

by Andre Kassis, 07/07/2019Introduction and Motivations

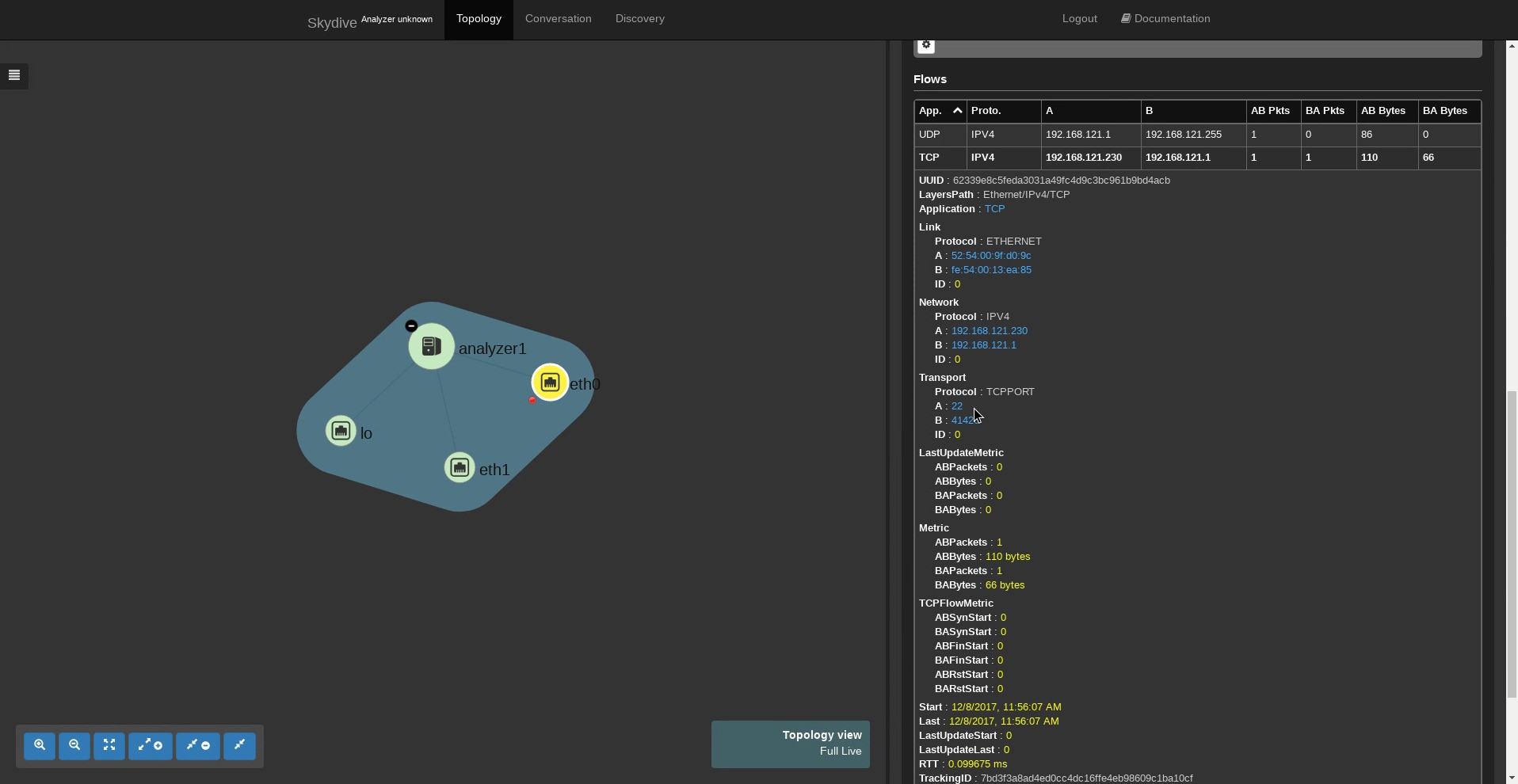

Skydive is an open source real-time network topology and protocol analyzer. It aims to provide a comprehensive way of understanding what is happening in the network’s infrastructure. To that end, Skydive collects data regarding the topology and the flows in the environment in which it is deployed and passes it to the user.

A flow is merely a connection (typically defined by a 5-tuple) between two endpoints that enables exchanging traffic over the internet. In a data center, the admin would typically aspire to collect information regarding such connections for various reasons, e.g., to ensure that certain security rules are being enforced, identify and debug network failures or even collect this data to perform further analysis and track specific protocols.

The flow probes that Skydive currently offers are:

- sFlow

- AFPacket

- PCAP

- PCAP socket

- DPDK

- eBPF

- OpenvSwitch port mirroring

Recently, our team has been experimenting with Skydive's eBPF probe, in an attempt to improve its performance and fix bugs in its internal implementation to enable Skydive's users to replace the currently used PCAP filter with eBPF, to obtain better performance and allow for a more fine-grained flow tracing.

Packet probes like PCAP and AFPACKET suffer from significant performance issues, for in order to extract the metadata from a particular packet, the latter must be copied to user-space. This entails a massive amount of unnecessary copies that slow down the system especially in cases where the packet's data is not needed, and we merely need the metadata to provide statistics and analysis for a given system, which is the typical case for Skydive's users.

The Magic of eBPF

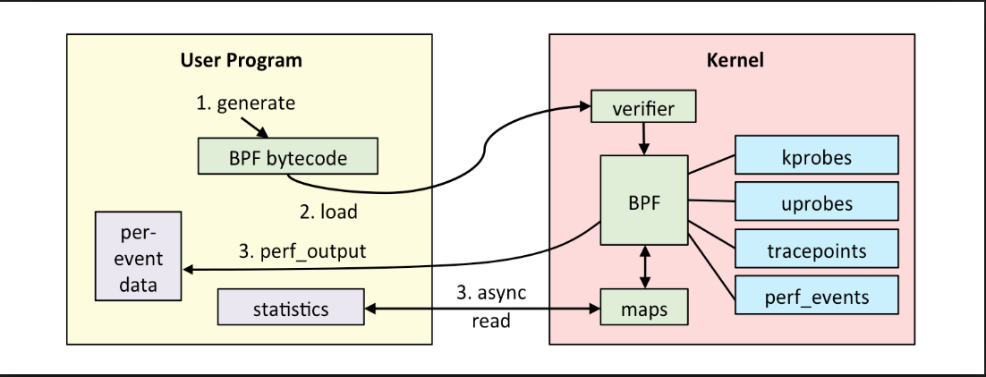

To address the above problem, we utilize a powerful tool that the Linux kernel provides – eBPF. eBPF (https://lwn.net/Articles/740157/) is a mechanism that allows programmers to dynamically write code and run it as part of the kernel to be triggered upon certain events, that in our case are new packets that are received at the kernel.

With the help of this powerful tool, we were able to write a custom packet probe that operates as follows:

-

Instead of copying each packet to user-space, the kernel maintains its own local flow table.

-

Upon the arrival of a new packet, the eBPF code is triggered, and the packet is processed, i.e., its metadata is extracted, and the flow to which it belongs is updated accordingly in the kernel's flow table.

-

In order to pass the flow data to the user-space, the kernel's flow table is queried periodically via the use of system calls that copy the flows from the kernel's table to a replica in the user-space.

Using the above algorithm, we reduce the number of unnecessary copies by millions, especially when the number of concurrent flows in the system is low, and the intercepted packets belong to a meager number of connections. The system now only copies the flow structure from the kernel and discards all the packets that belong to it since they have already been processed inside the kernel.

By doing so, the new bottleneck becomes the number of concurrent flows, rather than the number of packets per second. Therefore, to ensure the performance boost, we need to set the relevant parameters appropriately, and in this case, there are two key parameters:

- The flow table size inside the kernel

- The interval for scanning the kernel table

Setting the interval to be too short will result in a large number of copies and system calls that slow down the system, while a long interval will prevent the flow table from accepting new flows, for it will reach its maximum size and discard new incoming flows.

The flow table size is as crucial since it dictates the rate at which it should be flushed to the user-space. A large table will also exhaust the kernel memory.

Nowadays, it seems that a typical server (HTTP) serves, on average, around 50K requests per second. Therefore, we set the table size to 500K entries and the scan interval to 10 seconds, allowing us to handle 500K connections every 10 seconds, or equivalently, 50K connections/second. It is worth mentioning that Skydive exposes these two variables as configurable parameters – flow.max_entries and agent.flow.ebpf.kernel_scan_interval - And allows the users to change them as they see fit. However, we recommend that they remain unchanged (these are the default parameters and will be passed to the probes upon starting the capture unless the user specifies otherwise) since they are highly compliant with the demands from a real server and have proven to yield the best results in the benchmarking tests that we performed.

Evaluation

As mentioned above, the main challenge that the novel eBPF approach faces is the number of concurrent connections. In fact, it is almost agnostic to the rate at which new packets arrive, as opposed to other packet probes such as PCAP, AFPACKET, etc…

Hence, our test gradually increments the number of flows to detect the system's breaking point. The number of parallel connections ranges from 1 to 1M.

Settings

- We use a packet generator provided by Sylvain Afchain (https://gist.github.com/safchain/b86b9a6a42e7fcd17f6df1a0ca827ae3) to generate packets from one endpoint to another.

- The sender is placed in one host wholly isolated from the receiver (i.e., where Skydive is deployed)

- Skydive runs in two different pods, one for the agent and the other for the analyzer.

- We measure the CPU and memory consumption while the stress tests are running.

- We use the packet generator to set the number of flows on which the packets are sent and examine the effects this parameter has on the system.

- The test generates packets of 1024 bytes each (minimal, to maximize the number of context switches and simulate more severe stress).

- The only variable we change from one run to another is the number of connections.

Results & Analysis

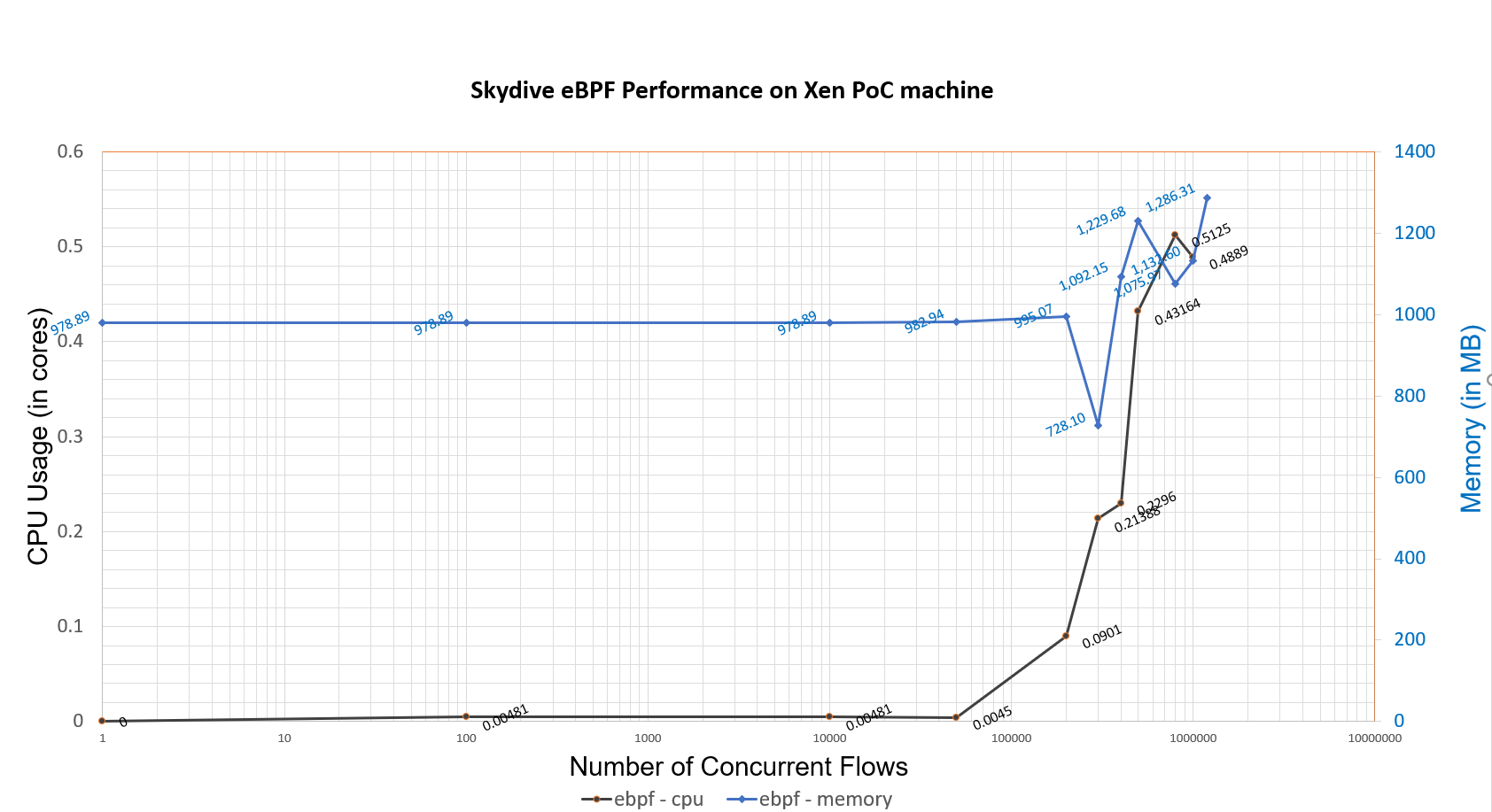

The numeric results are depicted in the graph below:

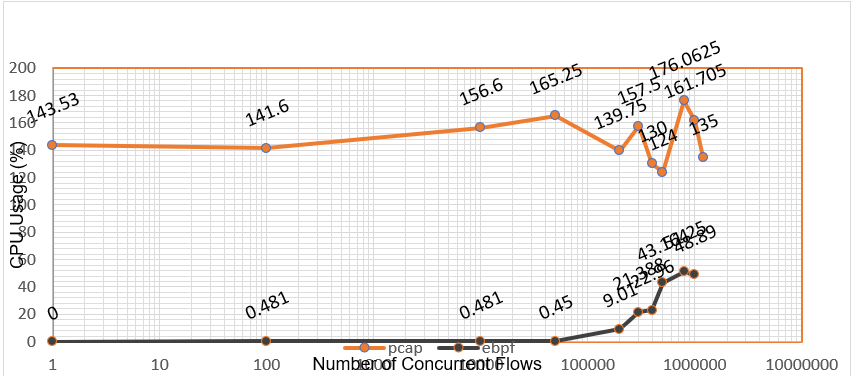

The graph below compares the CPU usage of the eBPF probe to that of PCAP:

- Running in eBPF mode, Skydive proves to be extremely efficient in terms of CPU and memory consumption.

- For a small number of flows, regardless of the number of packets per second (tens of millions in this case), almost no CPU is consumed. As the number of flows grows larger, Skydive starts to utilize more of the available CPU and hits a saturation point at ~500K flows, as expected.- This is the default table size, which was also used for testing. This number can be changed, as explained above.

- The CPU usage does not exceed 0.5 CPU cores.

- Skydive outperforms other widely used methods by far, such as PCAP and AFPACKET, whose performance depends highly on the rate at which packets are received and for a massive number of packets will require at least two cores.

Conclusions & Challenges

- The above results make it unequivocal that eBPF is the way to go. While other packet filters are expensive in CPU and memory, this probe can outperform the widely used methods, capture more packets and preserve correctness while its CPU and memory consumption remains low.

- The results also demonstrate the power of in-kernel packet filtering. The low CPU and memory usage of the eBPF packet probe show that there exist specific scenarios wherein kernel-level packet filtering can satisfy the system's demands without the need to use new expensive hardware.

- For typical stress, i.e., ~ 50K connections/second, eBPF outperforms other probes by far. Furthermore, in other realistic scenarios, where the number of connections is much lower, eBPF runs almost invisibly, while PCAP struggles to copy every received packet.

- That said, one must acquiesce in the fact that eBPF still comes with a price. When the stress exceeds the maximal that the system can handle (depends on the configuration parameters as described above) the kernel will start dropping packets, which in that case will be inevitable. However, this is a systematic flaw that will always exist and depends on how powerful the available resources in the system are. Moreover, our tests were designed to simulate significant stress that is also likely to exist, and the proposed eBPF probe was able to withstand the challenge and deliver the desired results. While more massive stress might exist, it is highly unlikely.

- The performance of eBPF code depends highly on the implementation of the code and its compliance with the system and its resources. It is the programmer's ability to ensure that the code functions appropriately and optimize it such that it achieves the best results. Developing the eBPF probe for Skydive has not been easy, and we had to deal with many issues that affected both the correctness and the performance of the code.

- As the recent results are highly satisfying, there still exists an area for further development. Currently, the Skydive team is working on making the probe even more efficient, and to that end, various approaches are being considered. One of the most promising approaches can be enabling BPF filtering from the eBPF code, to make it possible to drop irrelevant flows at the kernel level and before they populate the kernel table, to save kernel memory and reduce the number of copies to the user-space.

- One last important point to address in the future is eBPF's inability to provide data for specific protocols such as DNS, DHCP, etc… In order to provide application level information, the payload of each packet may need to be copied to the user-space, which is what this specific approach strives to eliminate.

How to Use

To learn how to deploy Skydive and start an eBPF capture, please refer to http://skydive.network. You can find the specific instructions on starting new captures at http://skydive.network/tutorials/first-steps-6.html. To start a new capture, follow the instructions available at this above link – the relevant command line would be:

skydive client capture create --gremlin 'G.V().Has("Name", "eth0")'However, in order to make it work with the eBPF probe and not the default PCAP, the command line would need to be extended as follows:

skydive client capture create --gremlin 'G.V().Has("Name", "eth0")' –-type ebpfAcknowledgments

We thank Sylvain Afchain, Sylvain Baubeau, Nicolas Planel, and Andre Kassis for their valuable contributions.